- The Roots of Graffiti

Graffiti is not a modern invention. Its roots go back to ancient civilizations, where people carved messages and drawings on cave walls or city ruins like Pompeii.

But the modern graffiti movement was born in New York City during the 1970s, when young people started writing their names and nicknames on subway trains and walls.

Names like Cornbread and Taki 183 became legendary — symbols of rebellion and identity.

Advertisement

Graffiti began as the voice of the voiceless — a cry for recognition and freedom.

2. The Types of Graffiti

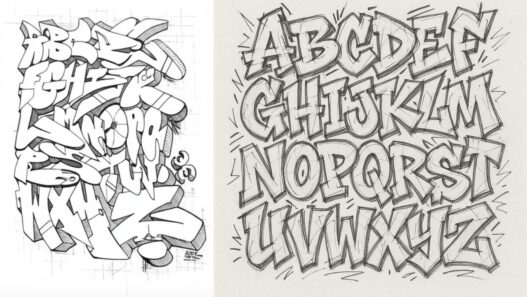

Graffiti has evolved into many unique forms and styles:

- Tag: a simple signature or name, the most basic form.

- Throw-up: bubble-style letters done quickly with two or three colors.

- Piece (Masterpiece): a detailed, colorful wall artwork that takes time and skill.

- Stencil: made using cut-out templates; popularized by artists like Banksy.

- Wildstyle: complex, interlocking letters — hard to read but full of energy.

- Character Art: drawings of faces, figures, or symbols mixed with lettering.

Each style represents a different purpose: fame, message, identity, or rebellion.

3. Human and Legal Perspectives

Graffiti always lives in a grey zone between art and crime.

- Human perspective:

Some see graffiti as a pure form of self-expression, a reflection of the city’s soul.

Others see it as vandalism, destroying public or private property. - Legal perspective:

In most countries, graffiti is illegal without permission.

However, cities like Berlin, Melbourne, and Lisbon have turned graffiti into a cultural movement, allowing artists to paint legally in specific zones.

The conflict lies between artistic freedom and property rights.

4. Graffiti and the Media

For decades, the media portrayed graffiti writers as criminals — the “bad kids” of the city.

But today, attitudes are changing. Magazines, documentaries, and art critics now view graffiti as urban art — a new visual language that speaks to social struggles and youth identity.

In political or oppressed areas, graffiti often becomes a weapon of resistance, carrying messages of truth, freedom, and justice.

The media can either destroy graffiti’s image or elevate it to a global art form.

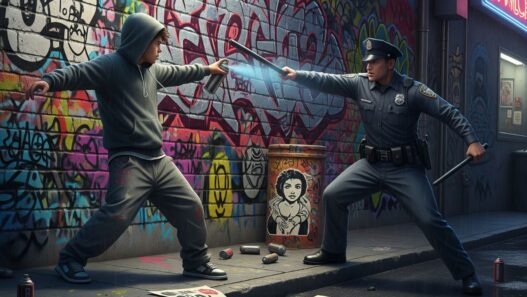

5. Graffiti and the Police

The relationship between graffiti artists and the police has always been tense.

Police see graffiti as a public disorder problem, while artists see it as a right to exist in public space.

In some cities, however, this relationship is changing — local governments are inviting graffiti artists to paint murals instead of chasing them away.

Between artist and officer, there’s always a wall — not of bricks, but of misunderstanding.

💭 Conclusion

Graffiti is more than paint on walls — it’s a reflection of society’s pulse.

It’s the art of rebellion, emotion, and identity.

Whether loved or hated, erased or celebrated — graffiti will always return, louder and stronger, because you can erase the paint, but not the voice behind it.

share botton: